Declarative and composable input validation with rich errors in Java

Abstract #

This proposal tackles input validation in Java with a functional Parser abstraction.

The Problem section describes input validation logic in MVC Controllers, and why manual validation logic is sub-optimal.

The Alternatives section explores existing solutions to this problem.

Solution - an example shows an example of the Parser abstraction in a simulated scenario.

Solution - a tutorial explains how the Parser abstraction can be derived, step by step.

Finally, the Implementation section describes the full Parser API and some

of its implementation details.

All source code is available at github.com/garciat/java-functional.

Problem #

In an MVC-style application that implements a Thrift server, a Controller's responsibility is to implement Thrift endpoints by accepting Thrift requests and delegate to domain services that implement the expected business logic.

Thrift requests are generally well-structured and well-typed. Despite this, Thrift types have two main issues:

- All Thrift Struct fields are

Nullable, even if they are marked ‘required’ in the IDL. - Thrift primitive types require parsing/transformation into proper Java types.

E.g.

java.util.UUID

Issue #1 leads to null-checking code (or overuse of Optionals). For example:

String transactionId = request.getTransactionId();

if (transactionId == null) {

return Task.failure(badRequest("Missing request.transactionId"));

}

Issue #2 leads to error handling code (usually try-catch blocks) when calling

parsing routines like java.util.UUID.fromString(String) or

java.date.Instant.parse(String). For example:

UUID paymentProfileUUID;

try {

paymentProfileUUID = UUID.fromString(request.getAccountId());

} catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

return Task.failure(badRequest("request.accountId is invalid"));

}

A (minor) issue that arises from this type of code is that, because we fail fast on each validation, calling APIs with many arguments can be a painful trial and error process. This is a reasonable trade off, however, because trying to accumulate errors in an ad-hoc manner in the controller would further exacerbate the above code issues.

Alternatives #

javax.validation #

javax.validation is a standard Java validation framework. It relies on

@Annotations to declaratively specify the requirements on each field of a

class. For example:

public class User {

@NotNull(message = "Name cannot be null")

private String name;

@AssertTrue

private boolean working;

@Size(min = 10, max = 200, message

= "About Me must be between 10 and 200 characters")

private String aboutMe;

@Min(value = 18, message = "Age should not be less than 18")

@Max(value = 150, message = "Age should not be greater than 150")

private int age;

@Email(message = "Email should be valid")

private String email;

// standard setters and getters

}

The problem with javax.validation is that it doesn’t produce any evidence that validation actually happened. For example, the above “email” field will be validated against the standard email format, but its type remains as String, so downstream code must simply trust that the value has been validated at some earlier point.

This approach is error-prone and can shift part of the burden downstream in the code.

Any approach with an interface similar to the one below will have similar shortcomings:

interface Validator<T> {

void validate(T input) throws ValidationException;

}

Solution - an example #

Imagine parsing these hypothetical Thrift types:

(Note: here I use lombok to define immutable POJOs.)

@Value

class ThriftThing {

@Nullable String uuid;

@Nullable String timestamp;

@Nullable String currencyCode;

@Nullable ThriftNested nested;

}

@Value

class ThriftNested {

@Nullable String name;

}

Into these target types:

@Value

class ProperThing {

UUID uuid;

Instant timestamp;

Optional<Currency> currency;

ProperNested nested;

}

@Value

class ProperNested {

String name;

}

First, we define some reusable basic type parsers:

Parser<String, UUID> uuidParser = Parser.lift(UUID::fromString);

Parser<String, Instant> instantParser = Parser.lift(Instant::parse);

Parser<String, Currency> currencyParser = Parser.lift(Currency::getInstance);

Then, this is how we define the parsers from the Thrift types to our target types:

Parser<ThriftNested, ProperNested> nestedParser =

ParserComposition.of(ThriftNested.class, ProperNested.class)

.required(ThriftNested::getName)

.build(name -> new ProperNested(name));

Parser<ThriftThing, ProperThing> thingParser =

ParserComposition.of(ThriftThing.class, ProperThing.class)

.required(ThriftThing::getUuid, uuidParser)

.required(ThriftThing::getTimestamp, instantParser)

.optional(ThriftThing::getCurrencyCode, currencyParser)

.required(ThriftThing::getNested, nestedParser)

.build(nested -> currency -> timestamp -> uuid ->

new ProperThing(uuid, timestamp, currency, nested));

And this is how we use the parser:

thingParser.parse(input)

.orElseThrow(err -> new BadRequest().setMessage(err.toString()));

For example when parsing a bad object where all the fields are invalid:

ThriftThing bad1 = new ThriftThing("123", null, "111", null);

The Parser will continue parsing if one of the fields fails. This allows the Parser to accumulate all the errors into a tree-like structure:

Either.failure(

ParseFailure.tag("ThriftThing",

ParseFailure.merge(

ParseFailure.tag("Nested", ParseFailure.message("value is null")),

ParseFailure.merge(ParseFailure.tag("CurrencyCode",

ParseFailure.exception(type=java.lang.IllegalArgumentException)),

ParseFailure.merge(ParseFailure.tag("Timestamp",

ParseFailure.message("value is null")),

ParseFailure.tag("Uuid",

ParseFailure.exception(

type=java.lang.IllegalArgumentException,

message="Invalid UUID string: 123")))))))

The ParseFailure data structure can the be formatted into a human-readable format:

Parsing type com.example.ThriftThing

Parsing field getNested

value is null

Parsing field getCurrencyCode

exception=java.lang.IllegalArgumentException

Parsing field getTimestamp

value is null

Parsing field getUuid

exception=java.lang.IllegalArgumentException message=Invalid UUID string: 123

On the other hand, when parsing a valid input Thrift object:

ThriftThing good =

new ThriftThing(

"1-1-1-1-1", "2020-05-20T10:23:31Z", null, new ThriftNested("hello"));

The successful result looks like this (that’s just the toString()

implementation of ProperThing):

Either.success(

ProperThing(

uuid=00000001-0001-0001-0001-000000000001,

timestamp=2020-05-20T10:23:31Z,

currency=Optional.empty,

nested=ProperNested(name=hello)))

Solution - a tutorial #

Parsing is validation #

Let's remember the sub-optiomal Validator interface:

interface Validator<T> {

void validate(T input) throws ValidationException;

}

In contrast to the Validator interface above, consider this Parser

interface:

interface Parser<T, R> {

R parse(T input) throws ParseException;

}

This interface will not only check that the input is valid and fail if it isn’t, but also it will produce A Valid Object as output.

For example:

A Parser<String, UUID> is a function that takes a String as an input,

validates its format and produces a UUID object that contains (and maintains,

through immutability!) the valid uuid information. If the String format is not

correct, the function will throw a ParseException.

A Parser<Optional<String>, String> is a function that takes a

Optional<String> and produces a String if the input is not empty.

You can imagine what these do:

Parser<String, Instant>Parser<ThriftRequest, DomainRequest>

Composition is key #

The reality is that more than one validation may apply to a single input. For example:

String accountId = request.getAccountId();

if (accountId == null) {

return Task.failure(new BadRequest().setMessage("request.accountId is missing"));

}

UUID paymentProfileUuid;

try {

paymentProfileUuid = UUID.fromString(accountId);

} catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

return Task.failure(new BadRequest().setMessage("request.accountId is invalid"));

}

The code first validates that accountId is not null, then it validates that a

UUID can be parsed from it.

The Parser abstraction must account for validation sequencing. In a way, it

already does:

Parser<Optional<String>, String> requiredStringParser = ...;

Parser<String, UUID> uuidParser = ...;

UUID paymentProfileUuid =

uuidParser.parse(

requiredStringParser.parse(

Optional.ofNullable(request.getAccountId()));

It is possible to manually thread the input & outputs of each parser to get the desired result.

If either parser throws a ParseException, because of how exceptions work, the

apparent effect is the same.

However, consider what would happen if the code used 4 parsers in succession:

xParser.parse(yParser.parse(zParser.parse(wParser.parse(input))))

Because of the order of evaluation of expressions, the sequence code reads inside-out:

-

wParser runs first, then zParser, then yParser, and finally xParser

Adding a composition operation can make the code more readable by reading left to right:

interface Parser<T, R> {

R parse(T input) throws ParseException;

<S> Parser<T, S> andThen(Parser<R, S> next);

}

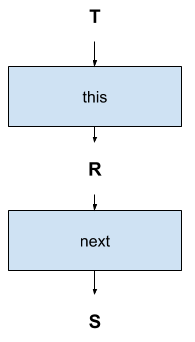

The andThen method of a Parser<T, R> takes a Parser<R, S> and

returns a

Parser<T, S>. This means that the output of Parser<T, R> is automatically

threaded to Parser<T, S>. The result is a new parser that can take T objects

as input and produce S objects as output.

Making use of the composition method:

Parser<Optional<String>, String> requiredStringParser = ...;

Parser<String, UUID> uuidParser = ...;

Parser<Optional<String>, UUID> requiredUuidParser =

requiredStringParser.andThen(uuidParser);

UUID paymentProfileUuid = requiredUuidParser.parse(Optional.of(request.getAccountId()));

Through Parser composition, a new reusable Parser was created without writing any implementation code. Also, the hypothetical 4 parser case now reads left to right:

wParser.andThen(zParser).andThen(yParser).andThen(xParser).parse(input)

Parsers out of thin air #

Because all Thrift getters return @Nullable objects, we are forced to deal

with null in every case. So this one bit of code is likely to repeat many times

when parsing Thrift:

Optional.of(request.getAccountId())

So far, Parser implementations have done “actual parsing work”. However, it can be useful to admit simpler parsers into the vocabulary.

For example, the getter ThriftRequest::getAccountId is a

Function<ThriftRequest, @Nullable String>. In a way, this can be seen as

“parsing” a @Nullable String out of the ThriftRequest. And this can be

represented with a Parser<ThriftRequest, Optional<String>> (while also

accounting for nulls with Optional).

Let’s introduce a “constructor” to the interface to represent the above fact:

interface Parser<T, R> {

R parse(T input) throws ParseException;

<S> Parser<T, S> andThen(Parser<R, S> next);

static <T, R> Parser<T, Optional<R>> liftOptional(Function<T, R> getter);

}

The method liftOptional takes a Function<T, R> and returns a

Parser<T, Optional<R>>. Remember that a Parser<T, Optional<R>>

is just a

function from T (input) to Optional<R> (output). So liftOptional is

simply

“changing the type” of the function into a Parser.

It is now possible to write:

Parser<Optional<String>, String> requiredStringParser = ...;

Parser<String, UUID> uuidParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, Optional<String>> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId);

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

accountIdParser

.andThen(requiredStringParser)

.andThen(uuidParser);

UUID paymentProfileUuid = accountIdParser.parse(request);

Notice how the types match between inputs and outputs:

Parsers for free #

Let's introduce some more methods and constructors to supercharge Parser

creation an composition:

interface Parser<T, R> {

R parse(T input) throws ParseException;

<S> Parser<T, S> andThen(Parser<R, S> next);

static <T, R> Parser<T, R> lift(Function<T, R> mapper);

static <T, R> Parser<T, Optional<R>> liftOptional(Function<T, R> getter);

static <T> Parser<Optional<T>, T> nonEmpty();

}

The lift method is similar to liftOptional, except it does not expect a

null output. It will also convert all exceptions thrown by the passed

Function and wrap them with a ParseException.

The nonEmpty method creates a new mapper that works for any type and ensures

that the input Optional is not empty.

So far we had omitted the definition of requiredStringParser and uuidParser.

It is now possible to tackle them with minimal code:

Parser<Optional<String>, String> requiredStringParser = Parser.nonEmpty();

Parser<String, UUID> uuidParser = Parser.lift(UUID::fromString);

Parser<ThriftRequest, Optional<String>> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId);

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

accountIdParser

.andThen(requiredStringParser)

.andThen(uuidParser);

UUID paymentProfileUuid = accountIdParser.parse(request);

Yes, that’s all.

The intermediate parsers can be inlined to get more condensed code:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId)

.andThen(Parser.nonEmpty())

.andThen(Parser.lift(UUID::fromString));

UUID paymentProfileUuid = accountIdParser.parse(request);

The compiler makes sure along the way that all types match.

Exceptions get in the way #

Hold on. The code above is not actually returning a BadRequest like the

original code. Let’s address that:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId)

.andThen(Parser.nonEmpty())

.andThen(Parser.lift(UUID::fromString));

UUID paymentProfileUuid;

try {

paymentProfileUuid = accountIdParser.parse(request);

} catch (ParseException e) {

return Task.failure(new BadRequest().setMessage(e.getMessage()));

}

Eek. That broke the compositional style and brought us back into imperative code.

Exceptions always get in the way.

An Optional detour #

The Optional type in Java is not just a glorified null value. Its real value

comes from turning a non-compositional construct (null) into a compositional

one (a normal object).

Consider the functions:

// returns empty string if the header is not found

String getHeader(Request request, String name);

// throws IllegalArgumentException if the parse fails

URI parseURI(String input);

// returns -1 if URI does not specify a port

int getPort(URI uri);

The functions above may fail, so code using them must handle the failure:

String referrerHeader = getHeader(request, "Referer");

if (referrerHeader == "") {

// jump out

}

URI referrer;

try {

referrer = parseURI(referrerHeader);

} catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

// jump out

}

int referrerPort = getPort(referrer);

if (referrerPort == -1) {

// jump out

}

Notice that the code doing actual work is obfuscated by the error handling code. Not only that, each function fails in a different way, so the code is not even uniform.

Optional to the rescue:

Optional<String> getHeader(Request request, String name);

Optional<URI> parseURI(String input);

Optional<Integer> getPort(URI uri);

The user code can then be simplified greatly:

int referrerPort =

getHeader(request, "Referer")

.flatMap(parseURI)

.flatMap(getPort)

.orElseThrow(/* jump out */);

The flatMap method of an Optional<T> takes a “continuation callback” of type

Function<T, Optional<U>>. Then it performs the logic: if the

Optional<T> is

empty, then return an empty Optional<U>. If the Optional<T> contains a

T,

pass that T to Function<T, Optional<U>> to get an

Optional<U> and return

that.

We can leverage Optional to handle failure in our Parser:

interface Parser<T, R> {

Optional<R> parse(T input);

}

Then the user code looks like:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId)

.andThen(Parser.nonEmpty())

.andThen(Parser.lift(UUID::fromString));

UUID paymentProfileUuid =

accountIdParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(() -> new BadRequest());

This is much neater.

It’s Either way #

The Parser returning Optional is neater, but now it is not possible to know

why the parse failed. An Optional’s empty case does not contain any context

for why it is empty:

interface Optional<T> {

static <T> Optional<T> of(T value);

static <T> Optional<T> empty();

}

Notice Optional::empty takes no arguments. We would like to provide a context

object when there is a failure parsing, and Optional::empty does not allow

this.

Enter the Either type:

interface Either<T, F> {

static <T, F> Either<T, F> success(T value);

static <T, F> Either<T, F> failure(F context);

}

Either<T, F> is just like an Optional<T>: when constructed in a “successful

state,” the Either contains an object of type T. The main difference is that

it also carries an object of type F when it is constructed in a “failure

state”.

Let’s adjust the Parser interface:

interface Parser<T, R> {

Either<R, ParseFailure> parse(T input);

}

Let’s also provide the Either type with a similar orElseThrow method:

interface Either<T, F> {

<E extends Throwable> T orElseThrow(Function<F, E> handler) throws E;

}

Then the client code can provide a meaningful error message:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser =

Parser.liftOptional(ThriftRequest::getAccountId)

.andThen(Parser.nonEmpty())

.andThen(Parser.lift(UUID::fromString));

UUID paymentProfileUuid =

accountIdParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

Composition is always the answer #

As code is migrated to use the Parser abstraction, an old issue will arise:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, ZoneId> contextTimezoneParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, InputCursor> cursorParser = ...;

UUID paymentProfileUuid =

accountIdParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

ZoneId timezone =

contextTimezoneParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

InputCursor cursor =

cursorParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

Because each Parser separately parses a single value and fails individually,

the code still ends up repeating the failure handling code:

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

This one’s a bit harder to explain, sorry. But the answer is composition (:

interface ParserComposition<T, R, F> {

Parser<T, R> build(F handler);

<S> ParserComposition<T, R, Function<S, F>> with(Parser<T, S> next);

static <T, R> ParserComposition<T, R, R> of(Class<T> input, Class<R> result);

}

Let’s go about this by observing the types:

x = ParserComposition.of(ThriftThing.class, DomainThing.class)

⇒ ParserComposition<

ThriftThing, DomainThing,

DomainThing>

y = x.with((Parser<ThriftThing, UUID>) accountIdParser)

⇒ ParserComposition<

ThriftThing, DomainThing,

Function<UUID, DomainThing>>

z = y.with((Parser<ThriftThing, ZoneId>) contextTimezoneParser)

⇒ ParserComposition<

ThriftThing, DomainThing,

Function<ZoneId, Function<UUID, DomainThing>>>

Notice how the type parameter F starts with the initial result type

DomainThing and ends up accumulating the output types of all the parsers

added, using the with method, as nested Functions.

When build is eventually called, its input parameter handler will require of

the caller this accumulated function:

Function<ZoneId, Function<UUID, DomainThing>> handler

= timezone -> accountId -> new DomainThing(timezone, accountId);

z.build(handler);

⇒ Parser<ThriftThing, DomainThing>

Then the client code looks like:

Parser<ThriftRequest, UUID> accountIdParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, ZoneId> contextTimezoneParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, InputCursor> cursorParser = ...;

Parser<ThriftRequest, DomainThing> domainParser =

ParserComposition.of(ThriftRequest.class, DomainThing.class)

.with(accountIdParser)

.with(contextTimezoneParser)

.with(cursorParser)

.build(cursor -> timezone -> accountId ->

new DomainThing(cursor, timezone, accountId));

DomainThing domainThing =

domainParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

With some additional helpers, we can get this code:

Parser<ThriftRequest, DomainThing> domainParser =

ParserComposition.of(ThriftRequest.class, DomainThing.class)

.required(ThriftRequest::getAccountId,

Parser.lift(UUID::fromString))

.required(ThriftRequest::getTimezone,

Parser.lift(ZoneId::of))

.required(ThriftRequest::getPaginationMetadata,

cursorParser) // delegate to another predefined parser

.build(cursor -> timezone -> accountId ->

new DomainThing(cursor, timezone, accountId));

DomainThing domainThing =

domainParser.parse(request)

.orElseThrow(failure -> new BadRequest().setMessage(failure.getMessage()));

And yes, that’s the full parser code.

Implementation #

A couple of notes:

- This may be slightly out of date. Please refer to the full code.

- The implementation differs slightly from the code described above:

- Field-based methods in

ParserCompositionwere extracted into a utility classFields.

- Field-based methods in

Either #

Several methods were added to aid in the implementation of Parser.

public abstract class Either<T, F> {

// "pattern match" on Either with two callbacks

public abstract <R> R match(Function<T, R> success, Function<F, R> failure);

// Semantic methods

public <E extends Throwable> T orElseThrow(Function<F, E> handler) throws E;

// Structural methods

public <U> Either<U, F> map(Function<T, U> mapper);

public <G> Either<T, G> mapFailure(Function<F, G> mapper);

public <U> Either<U, F> flatMap(Function<T, Either<U, F>> callback);

// Constructors

public static <T, F> Either<T, F> success(T t);

public static <T, F> Either<T, F> failure(F f);

public static <T> Either<T, Throwable> run(Supplier<T> supplier);

public static <A, B> Function<A, Either<B, Throwable>> lift(Function<A, B> func);

// Combinators

public static <F, A, B, C> Either<C, F> merge(

Either<A, F> eitherA,

Either<B, F> eitherB,

BiFunction<A, B, C> valueMerge,

BinaryOperator<F> failureMerge);

}

Functional concepts #

FunctorviaEither::mapApplicative FunctorviaEither::merge(with a merge operation forF)MonadviaEither::flatMap

ParseFailure #

This class forms a recursive tree-like structure that describes failure.

format() returns a human-readable form.

public abstract class ParseFailure {

public final String format();

// Constructors

public static ParseFailure message(String message);

public static ParseFailure exception(Throwable t);

public static ParseFailure tag(String tag, ParseFailure sub);

public static ParseFailure type(Class<?> type, ParseFailure sub);

public static ParseFailure getter(Getter<?, ?> getter, ParseFailure sub);

public static ParseFailure merge(ParseFailure left, ParseFailure right);

}

Parser #

public interface Parser<T, R> {

Either<R, ParseFailure> parse(T input);

// Semantic methods

default Parser<T, R> tagged(String tag);

// Structural methods

default <S> Parser<T, S> map(Function<R, S> mapper);

default <S> Parser<T, S> andThen(Parser<R, S> next);

default Parser<T, R> recoverWith(Parser<T, R> fallback);

default <S> Parser<T, R> flatMap(Function<T, Parser<T, S>> callback);

// Constructors

static <T> Parser<T, T> id();

static <T, R> Parser<T, R> returning(R r);

static <T, R> Parser<T, R> lift(Function<T, R> function);

static <T, R> Parser<T, Optional<R>> liftNullable(

NullableFunction<T, R> function);

static <T> Parser<T, T> predicate(Predicate<T> predicate, String failureMessage);

// Combinators

static <T, A, B, C> Parser<T, C> merge(

Parser<T, A> left,

Parser<T, B> right,

BiFunction<A, B, C> merger);

static <T, R> Parser<Optional<T>, Optional<R>> liftOptional(Parser<T, R> parser);

}

Parser::merge #

Runs two Parsers “in parallel” and merges their output with the provided

merger function. When both parsers fail, their failure objects are

concatenated with ParserFailure::merge.

static <T, A, B, C> Parser<T, C> merge(

Parser<T, A> left,

Parser<T, B> right,

BiFunction<A, B, C> merger) {

return input ->

Either.merge(

left.parse(input),

right.parse(input),

merger,

ParseFailure::merge);

}

Functional concepts #

FunctorviaParser::mapCategoryviaParser::idandParser::andThenApplicative FunctorviaParser::mergeAlternative FunctorviaParser::recoverWithMonadviaParser::flatMap

Parsers #

This utility class provides a collection of basic reusable Parser instances:

public final class Parsers {

private Parsers() {}

public static <T> Parser<Optional<T>, T> nonEmpty();

public static <T> Parser<Optional<T>, T> defaulting(Supplier<T> fallback);

public static Parser<String, UUID> uuid();

public static Parser<String, Currency> currency();

public static Parser<String, Instant> iso8601();

public static Parser<String, ZoneId> zoneId();

public static Parser<String, Locale> languageTag();

public static <T extends Number> Parser<T, T> positive();

// many more can be considered

}

Getter #

Makes use of reflection to provide information on the method reference used

to construct the Getter.

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Getter<T, R> extends NullableFunction<T, R>, Serializable {

default Info getInfo();

@Value

class Info {

String implClass;

String implMethodName;

public String getPropertyName();

}

}

Fields #

Constructs Parser instances from Getter instances, which are used to provide

failure diagnostics through Getter's refelection-based information.

public final class Fields {

private Fields() {}

public static <A, B> Parser<A, B> required(Getter<A, B> getter);

public static <A, B, C> Parser<A, C> required(Getter<A, B> getter, Parser<B, C> parser);

public static <A, B> Parser<A, Optional<B>> optional(Getter<A, B> getter);

public static <A, B, C> Parser<A, Optional<C>> optional(

Getter<A, B> getter, Parser<B, C> parser);

public static <A, B, C> Parser<A, C> optional(

Getter<A, B> getter, Supplier<C> fallback, Parser<B, C> parser);

/**

* To be used by Thrift fields with primitive types

*

* <p>For example, {@code optional(MyThrift::getInt, MyThrift::isSetInt, ...)}

*/

public static <A, B, C> Parser<A, C> optional(

Getter<A, B> getter, Predicate<A> hasValue, Supplier<C> fallback, Parser<B, C> parser);

}

ParserComposition #

This is the main class used by programmers to construct and compose Parsers.

public abstract class ParserComposition<T, R, F> {

public final Parser<T, R> build(F f);

protected abstract Parser<T, Parser<F, R>> build();

public <A> ParserComposition<T, R, Function<A, F>> with(Parser<T, A> field);

public static <T, R> ParserComposition<T, R, R> of(

Class<T> input,

Class<R> result);

}

ParserComposition::with #

This one’s hard to explain (:

The point is that it uses Parser::merge to compose parsers. Then all failure

is accumulated.

public abstract class ParserComposition<T, R, F> {

public <A> ParserComposition<T, R, Function<A, F>> with(Parser<T, A> field) {

return new ParserComposition<T, R, Function<A, F>>() {

@Override

protected Parser<T, Function<Function<A, F>, R>> build() {

Parser<T, Function<F, R>> parent = ParserComposition.this.build();

return Parser.merge(field, parent, (a, fr) -> af -> fr.apply(af.apply(a)));

}

};

}

}